|

Introduction

...Published in:

The Jurnal of Comparative Law

Volume XII, Issue One

ISSN: 1477-0814

Latest Release: June 26, 2018

Publisher: Wildy, Simmonds and Hill

Publishing

Country of Publication: UK

pp. 61-82

Mass atrocities

trials1 are like no other trials.

They are held, just as any other

criminal trial, to deliver justice

to victims, to punish perpetrators,

to mete out punishment and, by doing

so, to deter - or rather, to control

- the commission of crimes in

societies. But, unlike domestic

criminal trials, mass atrocities

trials have been invested with

expectations greater than

administering justice and delivering

judgments. They are supposed to have

an extralegal purpose: to establish

the truth about a conflict, to

create a historical record, to

contribute to the creation of a

historical narrative, and to help in

the shaping of collective memory.

In the past two decades doctrinal

literature on the legal and

extralegal purposes of mass

atrocities trials has grown rapidly,

proportionate to the number of

international criminal courts that

came into existence after the end of

the Cold War.2 These courts - ad hoc

and permanent - have processed over

a hundred trials, many of which

concluded with a judgment, whereas

some have remained unfinished,

mostly because defendants died

before the end of the trial.3 Most

judgments were convictions, and some

were acquittals.

This article addresses the interplay

between legal and extralegal

purposes of mass atrocities trials

by using a sample of the trials of

political and military leaders held

at the International Criminal

Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia

(ICTY).4

The point of departure is the

assumption that a courtroom always

becomes the place of importance for

establishing the truth, for

producing a historical record, and

for contributing to the historical

narrative of the conflict. But what

kind of truth, what kind of

historical record, and what kind of

historical narrative can be

expected?

In order to answer these questions

the following sub-questions are

addressed: (1) what is the

difference between “trial truth” and

“real truth”; (2) what constitutes a

trial record; (3) what sort of

contribution to the historical

narrative and collective memory can

one expect from judgments –

convictions, judgments on pleas of

guilty or acquittals; (4) can an

unfinished mass atrocities trial –

without a judgment rendered – be a

valuable historical source that

contributes to the historical

narrative?

This article first explores the

debate among practitioners at the

international criminal courts, legal

scholars, victim communities, and

post-conflict political elites on

the interplay between the legal and

extralegal objectives of mass

atrocities trials. Then we turn to

what sort of truth, historical

record, and historical narrative a

mass atrocities trial can produce.

The next section examines the

limitations that legal form can

create in relation to historical

narrative because of prosecutorial

discretion about whom to indict for

which crimes and according to which

principles of responsibility. The

limitations that rules of

admissibility of evidence can have

on the historical narrative when

some evidence of importance is

excluded or obscured from public

view on a legal basis are

considered. The final section

discusses whether there is any value

left, other than legal, for an

unfinished trial. How might the

trial archive of the unfinished

trial contribute to historical

justice and to the historical

narrative?

DOCTRINAL DEBATE ON LEGAL AND

EXTRALEGAL PURPOSES

OF MASS ATROCITIES TRIALS

The debate about the purpose of mass

atrocities trials extends to the

Nuremberg and the Tokyo Tribunals5

and has been dominated by two

opposing views.6 The tone in the

discussion on the purpose of a mass

atrocities trial was set by Hannah

Arendt (1906-1975), who argued that

mass atrocities trials should

fulfill their legal mandate and

nothing else. The debate about the purpose of mass

atrocities trials extends to the

Nuremberg and the Tokyo Tribunals5

and has been dominated by two

opposing views.6 The tone in the

discussion on the purpose of a mass

atrocities trial was set by Hannah

Arendt (1906-1975), who argued that

mass atrocities trials should

fulfill their legal mandate and

nothing else.

Reporting in 1961 from Jerusalem on

the Eichmann trial, Arendt wrote

“that the purpose of a trial is to

render justice, and nothing else;

even the noblest of ulterior

purposes … can only distract from

the law’s main business: to weigh

the charges brought against the

accused, to render judgment, and to

mete out punishment”.7 Decades later

when writing about the Tokyo

Tribunal, Ian Buruma went a step

further by arguing that there is no

place for history in the courtroom:

“Just as belief belongs in church,

surely history belongs in school”.

He concluded that “when the court of

law is used for history lessons,

then the risk of show trials cannot

be far off”.8 A practitoner at the

international criminal tribunals has

more recently argued that historical

record “can only be a by-product of

the trials where the emphasis must

necessarily be in determining

whether the Prosecution has

established the guilt of the accused

beyond reasonable doubt”.9

Their views stood in sharp contrast

to the words uttered by Hartley

Shawcross (1902-2003), the British

Chief Prosecutor at the Nuremberg

Tribunal who stated: “[W]e believe

that this Tribunal ... will provide

a contemporary touchstone and an

authoritative and impartial record

to which future historians may turn

for truth, and future politicians

for warning”.10

A growing consensus is in evidence

among scholars across different

fields in accepting the

complementarity between legal and

extralegal purposes of mass

atrocities trials. Lawrence Douglas

has introduced the term “didactic

legality”, arguing that trials of

the Holocaust blurred the boundary

between the legal and extralegal.11

While recognizing that the primary

responsibility of a criminal trial

is to resolve questions of guilt in

a procedurally fair manner, Douglas

advocates the integration of the

legal and extralegal purposes of

mass atrocities trials.12 Bilsky warns

against compartmentalising the

discussion into the legal versus the

historical. In her view, this

polarization distracts from the fact

that a transformative trial should

“fulfil an essential function in a

democratic society by exposing the

hegemonic narrative of identity to

critical consideration.”13 Bilsky sees

transformative trials as placed

somewhere between the political and

the legal.14 On one hand, she argues,

a transformative trial has to remain

loyal to the basic liberal values of

the rule of law, and, on the other

hand, it performs a unique function

as a legal forum in which society’s

fundamental values can be examined

in the light of competing counter

narratives as presented in the

courtroom.15

But what is the relationship between

legal and historical truth; between

legal and historical justice; and

between legal and historical

narrative? Does historical justice

exist at all? Teitel lists five

conceptions of justice: criminal

justice, historical justice,

reparatory justice, administrative justice, and

constitutional justice.16 She argues

that the pursuit of historical truth

is embedded in a framework of

accountability and in the pursuit of

justice, to which criminal trials

contribute.17 In defining historical

justice, Teitel applies the

Enlightenment view, in which history

is considered teacher and judge, and

historical truth is equated with

justice.18 Teitel cautions that when

history takes its “interpretative

turn”, there is no single, clear,

and determinate understanding or

lesson to draw from the past.

Instead, one must recognize the

degree to which historical

understanding depends on political

and social contingencies.19 Should we

look for one single truth and one

authoritative historical narrative

about past abuses at all? Or is it

realistic to expect that many

versions of a troubled and complex

past will always (co)exist with or

without trial archives?

MASS ATROCITIES TRIALS, TRUTH,

HISTORICAL RECORD,

AND HISTORICAL

NARRATIVE

Limitations of Adversarial Legal

Systems to Produce the Truth:

“Trial

Truth” vs “Real Truth”

“What is the truth?” is a

philosophical question. The fact

that there are different kinds of

truth – to start with a “historical

truth” and “trial truth” – is

confusing. Fergal Gaynor, a

barrister with longstanding working

experience at the international

criminal courts, finds that the

“extent to which a criminal trial is

essentially a truth-finding exercise

is on the philosophical fault-lines

which divide the inquisitorial and

adversarial systems”.20 The starting

point for understanding the notion

of “trial truth” is that a trial

held under the adversarial legal

regime produces at least two

competing narratives – the

prosecution narrative and the

defence narrative – as to how a

conflict turned violent and who was

to blame. Generally speaking, the

inquisitorial model (also known as

European or civil law systems) seeks

to come as close as possible to the

truth, whereas the adversarial model

(Anglo-Saxon legal systems) is more

about following rules in presenting

the evidence so as to preserve the

fairness of the trial and ensure

that convictions only follow proof

by evidence and argument of

allegations made.21

The truth as produced at the trials

presided over by Bert Röling

(1906-1985), the Dutch judge at the

Tokyo Tribunal, led him to conclude

that the many rules adopted

originally to protect the lay jury

from misleading and untrustworthy

evidence do not produce “real truth”

but a “trial truth”.22 Modern day

lawyers still voice the same

concerns. Sir Geoffrey Nice, the

lead prosecutor of Serbia’s

President Slobodan Milošević at the

ICTY, expressed his reservations

about the adversarial model being

the most efficient to prosecute mass

atrocities. He explained how it can

happen that judges compile judgments

based on two opposing narratives -

prosecution and defence - neither of

which might be an accurate, or even

a truthful, interpretation of facts

and events. Yet the judges may have

little choice but to make their

final determination based on the

persuasivness of the evidence and

legal arguments of one side and

produce a judgment that will not

tell the whole truth or the truth at

all.23 The truth as produced at the trials

presided over by Bert Röling

(1906-1985), the Dutch judge at the

Tokyo Tribunal, led him to conclude

that the many rules adopted

originally to protect the lay jury

from misleading and untrustworthy

evidence do not produce “real truth”

but a “trial truth”.22 Modern day

lawyers still voice the same

concerns. Sir Geoffrey Nice, the

lead prosecutor of Serbia’s

President Slobodan Milošević at the

ICTY, expressed his reservations

about the adversarial model being

the most efficient to prosecute mass

atrocities. He explained how it can

happen that judges compile judgments

based on two opposing narratives -

prosecution and defence - neither of

which might be an accurate, or even

a truthful, interpretation of facts

and events. Yet the judges may have

little choice but to make their

final determination based on the

persuasivness of the evidence and

legal arguments of one side and

produce a judgment that will not

tell the whole truth or the truth at

all.23

Otto Kirchheimer (1905-1965)24

advanced the theory of “double

wager” for mass atrocities trials

where polarized accounts of the past

are presented by prosecution and

defence.25 Kirchheimer’s theory was

that even if a trial ends in a

conviction, it may fail in its

didactic aim because the narrative

of the defendant might nevertheless

prevail. This risk becomes greater

when two or more persons are on

trial for the same or similar

crimes.26 Scholars who studied the

prevailing narratives in the

Holocaust trials found that the law

succeeded at times but, at others,

lost this wager.27

Courtroom History

How did the “double wager” work at

the ICTY? The ICTY’s indictments and

trials show that the majority of

those indicted were Serb nationals.

This was the outcome of the

investigation of the crimes that

were committed during the wars in

Croatia (1991-1992 and 1995), Bosnia

and Herzegovina (1992-1995), and

Kosovo (1998-1999). The majority of

the victims in those wars were

non-Serbs who lived within the Serb

designated territories - the term

used by the ICTY Prosecution to

denote the aspiration by Serb

leadership to create a post-Yugoslav

Serb ethnic State. Two of the Serbs

indicted, Radovan Karadžić and

Slobodan Milošević (1941-2006), were

the highest-ranking politicians ever

indicted by the ICTY.28 It is

noteworthy that before the ICTY was

formed in May 1993, the majority of

analysts, historians, and diplomats

had singled out the Serb side as

most responsible for the start of

the war and the commission of

crimes. But, there was also a

counter narrative that saw Serbia

and the Serbs as the victims of the

conspiracy led by the international

community and the former Yugoslav

republics – Slovenia and Croatia –

to destroy Yugoslavia as a State.

The same competing narratives were

repeated in the courtroom: the first

by the prosecution and the latter by

the defense.

The trial of Milošević was broadcast

daily in the region. Milošević, who

also defended himself in the court,

understood the importance of his

courtroom time and was busy

addressing his home audience by

showing contempt and haughtiness

towards the judges, prosecutors, and

occasionally towards prosecution

witnesses.29 He seemed to be aware of

the power of the “court of public

opinion” as he offered a televised

counter-narrative that he knew would

be well received in Serbia, saying

on one occasion:

In the international public, for a

long time and with clear political

intentions an untruthful, distorted

picture was being created in terms

of what happened in the territory of

the former Yugoslavia. Accusations

levelled against me are an

unscrupulous lie and also a tireless

distortion of history. Everything

has been presented in a lopsided

manner so – in order to protect from

responsibility those who are truly

responsible and to draw the wrong

conclusions about what happened and

also in terms of the background of

the war against Yugoslavia.30

The Milošević trial perpetuated the

contested narratives that existed

before the trial started. Those

pre-existing narratives were

sustained throughout the trial

because of the adversarial legal

procedures.

Judgments, Historical Record and

Historical Narrative

Do judgments reduce disputes over

historical narratives? Do they

establish a history closer to truth?

Are they “second drafts of history”,

as some authors claim.31 In the early

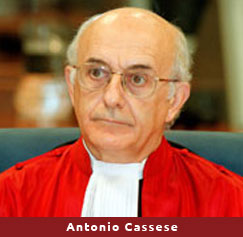

years of the ICTY with the first

judgment delivered, the presiding

judge Antonio Cassese (1937-2011)

expressed an expectation that the

judgment would deliver judicial

facts that “no revisionism or

amnesia” could erase.32 How does this

noble objective work in reality? Is

a judgment the ultimate goal of

justice? Or can the judgments

sometimes fail to achieve justice

and thus compromise the historical

truth and cement existing polarized

historical narratives? Or can they,

especially when quoted selectively

and out of context, sometimes serve

as powerful arguments in the hands

of deniers of past crimes? Do judgments reduce disputes over

historical narratives? Do they

establish a history closer to truth?

Are they “second drafts of history”,

as some authors claim.31 In the early

years of the ICTY with the first

judgment delivered, the presiding

judge Antonio Cassese (1937-2011)

expressed an expectation that the

judgment would deliver judicial

facts that “no revisionism or

amnesia” could erase.32 How does this

noble objective work in reality? Is

a judgment the ultimate goal of

justice? Or can the judgments

sometimes fail to achieve justice

and thus compromise the historical

truth and cement existing polarized

historical narratives? Or can they,

especially when quoted selectively

and out of context, sometimes serve

as powerful arguments in the hands

of deniers of past crimes?

In August 2016, some five months

after the prounouncement of the ICTY

Karadžić judgment , Deputy Prime

Minister and Minister of Foreign

Affairs of Serbia Ivica Dačić stated

in the media that the ICTY Karadžić

judgment exonerated former President

Slobodan Milošević and the state of

Serbia from any criminal

responsibility for mass atrocities

committed in Bosnia and Herzogovina.33

To support this assertion Minister

Dačić cited an online article in

which the author quoted selected

paragraphs from the judgment; he

argued that these exonerated

Milošević.34 The “news” on the

exoneration of Milošević spread

further via some well distributed

online publications.35

What do the cited paragraphs

actually contain? Paragraph 3460 on

page 1,303 states that Milošević

provided assistance in personnel,

provisions, and arms to Bosnian

Serbs during the conflict.36 The same

paragraph also concludes that there

was no sufficient evidence to prove

that Milošević had agreed with the

common plan; that is, the plan to

create the ethnically homogeneous

Serb territories in Bosnia and

Herzogovina cleansed of non-Serbs.

The quoted paragraph might read as a

negative statement about

insufficency of evidence and in no

way an assertion of Milošević’s –

let alone Serbia’s – proven

exoneration.

Minister Dačić added that the quoted

paragraph also exonerated the State

of Serbia.37 His words resonated in

the region. He was not just any

representative of the Serbian

government; he was a politician who

was responsible for the revival of

the Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS),

the party Milošević had founded in

1990. Once nicknamed by the media as

Mali Slobo (Little Slobo) for his

admiring imitation of Slobodan

Milošević, Dačić took over the

leadership of the SPS in 2006 and

since 2008 the SPS has been a

coalition partner in all subsequent

governments of Serbia, continuing

the political legacy of Milošević.

In legal parlance it may be

described as an “immaterial

averment” – something not needed to

be proved in order to convict

Karadžić.

Trial Archive as a Tool to Counter

Deniers?

When the former ICTY judge, Patricia

Wald, wrote in 2008 about the

aspiration of international courts

“to record for history an account of

war crimes as a hedge against future

disclaimers that they never happened

at all”,38 she did not mention the

problem of management of the vast

volume of the material every trial

produces for an outside user. Trial

archives of modern mass atrocities

trials are vast to the point of

being effectively impossible to

search and thus more or less

incomprehensible to outside users

who might want to turn to them for

infomation. The Karadžić judgment is

2,590 pages long, and the judgments

in the trials of two or more accused

can be even longer.

The ICTY judges in the ICTY Judgment

rendered in the case of the Serb

General Ratko Mladić went further

than the judges in the Karadžić case

in finding no links between General

Mladić and the members of the JCE

from Serbia. In paragraph 4238 of

the Mladić ICTY Judgment rendered on

22 November 2017, the Trial Chamber

found “that there was a plurality of

persons including the following

individuals: Radovan Karadžić,

Momčilo Krajišnik, Biljana Plavšić,

Nikola Koljević, Bogdan Subotić,

Momčilo Mandić, and Mićo Stanišić.”39

All named individuals were officials

from Republika Srpska. Whereas the

judges in the Karadžić case found

that the evidence confirmed that

Jovica Stanišić, Franko Simatović,

Željko Ražnatović and Vojislav

Šešelj - the politicians and state

officials from Serbia - did share

the common plan in Bosnia and

Herzogovina, the judges in the

Mladić case did not find enough

evidence that these individuals

participated in the realization of

the common criminal objective in

Bosnia and Herzogovina. The judges

in both trials agreed

that the evidence did not show that

Slobodan Milošević participated in

the realization of a commonly shared

criminal objective.40

Deniers of the crimes charged are

likely to be able to find in the

massive trial archives as well as in

court judgments of such length,

enough factual details or commentary

or even a paragraph from a judgment

taken out of context material on

which to construct, advance or

support an apologetic historical

narrative, regardless of the

verdict.

For example, how could outside

research find any relevant evidence

in the Milošević trial about a

“common plan”?41 Some valuable

evidence came from “insider”

witnesses and from the

contemporaneous records of high

level meetings that were acquired

from the State archives of Serbia

for the purpose of connecting

Milošević to the “common plan” for

Bosnia and Herzogovina. For example,

in the heat of the war in Bosnia and

Herzogovina, where the Serbs were

seizing territory by commission of

crimes,42 representatives from Serbia,

Republika Srspka (RS), a Serb entity

in Bosnia and Herzogovina, and

Republika Srpska Krajina (RSK), a

Serb entity in Croatia, held a

meeting at which Milošević stated as

a common goal the unity of Serbs

from Serbia, RS, and RSK:

We de facto have that because

objectively and according to our

relations, such as political,

military, economy, cultural and

educational, we have that unity. The

question is how to get the

recognition of the unity now,

actually how to legalise that unity.

How to turn the situation, which de

facto exists and could not be de

facto endangered, into being de

facto and de jure?43

By 1994, nothing had changed in his

thinking. Despite the formal rift

with the RS leadership as of August

1994, which has been cited as

relevant in the Karadžić judgment,

Milošević, summarizing Serb

political designs for Bosnia and

Herzogovina at a SDC meeting on 30

August 1994, cited a “unanimous

policy” among Serbs in the FRY,

Bosnia and Herzogovina, and Croatia,

revealing that Serb leaders had

indeed shared a common plan, as

alleged by the prosecution in the

Milošević case:

By pursuing a unanimous policy, and

quite successfully in my mind, we

have managed to save [the FRY] from

war, and at the same time rendered

as much support as possible to our

people across the Drina in creating

Republika Srpska, in creating the

Republika Srpska Krajina, and in

winning them a normal status in the

negotiations leading to an ultimate

goal, which now even the

international community has offered

to recognise. And that is

RepublikaSrpska, stretching over a

half of the territory of the former

Bosnia and Herzegovina!44

Milošević explained that the real

victory of the war in Bosnia and

Herzogovina was to see territorial

conquests recognized by the

international community. He said

that Serb conquests were “the

maximum that many have never even

dreamed of”.45 In order to achieve

ethnic separation in Bosnia and

Herzogovina between the Serbs and

two other ethnic groups – the

Bosnian Muslims and Croats – Serb

armed forces committed grave crimes.

Milošević was on record admitting

that without the war, ethnic

separation in Bosnia and Herzogovina

would have not been possible.46

When Minister Dačić tried to use the

Karadžić judgment for political

purposes, his attempt backfired as

the attention of the media in Bosnia

and Herzogovina and Croatia turned

to Dačić’s own role in the events

leading to the war in the 1990s.47

Minister Dačić's contribution to

Serbia's preparation for the war in

Bosnia and Herzogovina from 1992 had

been evidenced in the Milošević’s

trial. The evidence came from “open

sources”, a journal Epoha published

in Belgrade by the governing

Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS). The

Epoha issue of 7 January 1992,

included an article entitled

"Yugoslavia for the Third Time". The

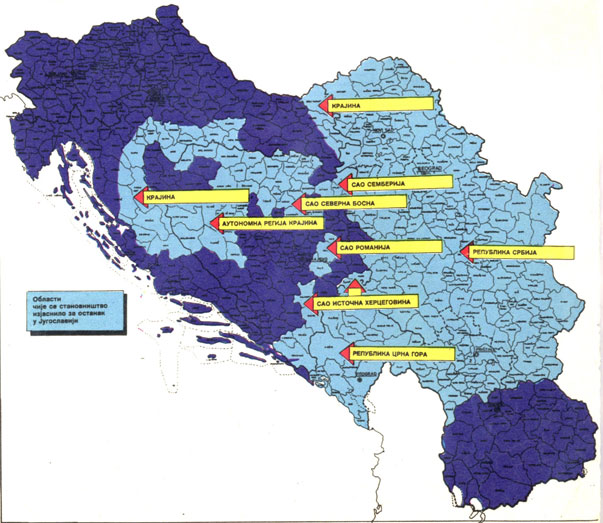

1992 article incorporated a

tell-tale map of Bosnia and

Herzogovina.48 The map depicted the

designated “Serb municipalities” in

Bosnia and Herzogovina, showing the

municipalites in which a majority of

Bosnian Serbs voted in the November

1991 referendum vote to stay in

Yugoslavia. The results of that

referendum were then used as a

demarcation of the Serb designated

territories in Bosnia and

Herzogovina. The 1992 Epoha map

roughly presented the projected

western border of the designated

Serbian State. In the subsequent war

in Bosnia and Herzogovina that would

start three months later, the Serb

armed forces targeted almost all

those “Serb municipalities” marked

on the 1992 Epoha map in order to

achieve ethnic separation in the

Serb designated territories. When Minister Dačić tried to use the

Karadžić judgment for political

purposes, his attempt backfired as

the attention of the media in Bosnia

and Herzogovina and Croatia turned

to Dačić’s own role in the events

leading to the war in the 1990s.47

Minister Dačić's contribution to

Serbia's preparation for the war in

Bosnia and Herzogovina from 1992 had

been evidenced in the Milošević’s

trial. The evidence came from “open

sources”, a journal Epoha published

in Belgrade by the governing

Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS). The

Epoha issue of 7 January 1992,

included an article entitled

"Yugoslavia for the Third Time". The

1992 article incorporated a

tell-tale map of Bosnia and

Herzogovina.48 The map depicted the

designated “Serb municipalities” in

Bosnia and Herzogovina, showing the

municipalites in which a majority of

Bosnian Serbs voted in the November

1991 referendum vote to stay in

Yugoslavia. The results of that

referendum were then used as a

demarcation of the Serb designated

territories in Bosnia and

Herzogovina. The 1992 Epoha map

roughly presented the projected

western border of the designated

Serbian State. In the subsequent war

in Bosnia and Herzogovina that would

start three months later, the Serb

armed forces targeted almost all

those “Serb municipalities” marked

on the 1992 Epoha map in order to

achieve ethnic separation in the

Serb designated territories.

This correlation of evidence

delivered a powerful example of how

a trial record could be used to

counter the deniers of past crimes.

But the same example also signals

the problem of how lengthy judgments

of thousands of pages in addition to

hundreds of thousands of pages of

evidence – which are not readily

accessible to journalists and

outside users - make the work of

deniers easier than it should be.

Source: ICTY, Exhibit P808a

(Prosecution v. Slobodan Milošević,

IT-02-54). The light color shows

municipalities in Croatia and Bosnia

and Herzogovina where the Serb

population voted to stay in a

Yugoslavia. These territories formed

the basis of Serbia’s attempt to

secure these territories and add

them to the new State that was

formed in 1992 by Serbia and

Montenegro and called the Federal

Republic of Yugoslavia (1992-2003).

LIMITATIONS OF LEGAL FORM TO PRODUCE

COMPREHENSIVE

HISTORICAL NARRATIVE

Prosecutorial Discretion in Deciding

Whom to Prosecute,

For Which Crimes

and on Which Legal Theory

In some cases, an indictment and

subsequent trial can lead to what

could be termed either

“under-prosecution” or

“over-prosecution” if the defendant

faces an indictment that is too

narrow or too broad in temporal or

geographical scope or gravity when

compared with what really happened.

Where the prosecution, for whatever

reason, “under prosecutes”49 or “over

prosecutes”,50 the State and all those

responsible in the apparatus of the

State may escape altogether,

especially if one individual is

“over-prosecuted” and is said – with

the authority of the prosecution –

to have been personally responsible

for all that happened.

The historical narrative may be

corrupted as a result. But if such a

chosen defendant stands trial only

to be acquitted at its conclusion,

that may have significant impact on

the legal and historical narrative.

The risks of over- or

under-prosecuting are perhaps at

their greatest in indictments

charging political and military

leaders for mass atrocities that

took place over a long period of

time. The lawyers have to be careful

not to overstate or understate the

powers of one single individual as

political and military plans are

usually conceived without a single

originator. Typically they may be

formed in cabinets, in war cabinets,

during private conversations between

leaders, even in public discussion

in the media. Rarely does one

individual formulate and put into

effect a plan all on his own. With

this reality in mind, the legal

doctrine of Joint Criminal

Enterprise (JCE) plays a significant

role. The doctrine resembles what is

termed a “conspiracy” in some

national legal systems.51 The doctrine

serves to link crimes to several, at

times many, individuals who

participated as perpetrators of

crimes, or who acted as instigators,

accomplices, or planners. While

connecting some individuals to the

commission of actual crimes, for

example the killing of civilians,

the doctrine allows forensic

consideration of the interactions

between – and cooperation among –

all the individuals who may be

members of a group or organization,

and who may simply have acted in

concert, for the purposes of the

JCE.52

The scope of the doctrine includes

“common purpose”, where the members

of a JCE – whatever their actual

involvement in the commission of the

crimes – shared a common

understanding of its goals. At the

ICTY, different levels of

participation in a JCE were

recognized; but each level required

JCE members to have shared a common

criminal purpose and to have, at a

minimum, knowledge that crimes were

being committed by others. Critics

of the doctrine point to its

inability to account for

“(co)responsibility in case of

functional fragmentation where the

lines of communication between the

accomplices are diffuse or are even

completely obliterated”. But these

criticisms overlook the realities of

how mass atrocities can be directed

without puppeteer strings being

visible. And the law – with all its

technical rules and doctrines – is

expected to disclose the complex

realties behind the crimes.

At the ICTY, separate but connected

trials were often treated

differently depending on the

decisions made by the Chief

Prosecutor or by a prosecution trial

team leading a case. For example, in

some indictments names of

individuals feature as members of a

joint criminal enterprise despite

none of the mentioned individuals

ever being indicted. Equally, some

individuals who were never mentioned

in any other ICTY indictment as

members of a JCE have been indicted

and tried. Once the crimes alleged

against an individual have been

charged and the indictment

confirmed, those charges or “counts”

in the indictment will have a major

influence on the trial and

eventually on the judgment. The same

accused might be found guilty of

some counts in the indictment but

acquitted of others. An additional

problematic reality is that

different trial chambers of the same

tribunal or court might ascribe

different value to evidence they

have heard on similar or identical

topics and come to different

conclusions about relevant

historical events. How can a

historian evaluate an indicment and

a related judgment and decide when

an indictment or a judgment or both

might be flawed.

Flawed Indictment or Flawed

Judgment?

General Perišić, the Chief of Staff

of the Army of Yugoslavia from 1993

to 1998, was indicted for crimes

that happened on the territory of

Bosnia and Herzogovina from 1992 to

1995. He had been indicted for

aiding and abetting crimes committed

by the Serbian Army of Krajina

(Srpska vojska Krajine – SVK) in

Croatia and by the Bosnian Serb Army

(Vojska Republike Srpske – VRS) in

Bosnia and Herzogovina, but was

never named as a member of any JCE

in any related ICTY indictment.

Perišić’s indictment – for some

reason - did not include the JCE

legal doctrine at all. General Perišić, the Chief of Staff

of the Army of Yugoslavia from 1993

to 1998, was indicted for crimes

that happened on the territory of

Bosnia and Herzogovina from 1992 to

1995. He had been indicted for

aiding and abetting crimes committed

by the Serbian Army of Krajina

(Srpska vojska Krajine – SVK) in

Croatia and by the Bosnian Serb Army

(Vojska Republike Srpske – VRS) in

Bosnia and Herzogovina, but was

never named as a member of any JCE

in any related ICTY indictment.

Perišić’s indictment – for some

reason - did not include the JCE

legal doctrine at all.

The only names mentioned were of his

subordinate officers who were sent

by the Yugoslav Army (Vojska

Jugoslavije – VJ) to fight for the

Army of Republika Srpska (Vojska

Republike Srpske – VRS), many of

whom have been tried and some

convicted by the ICTY.53 Neither

General Perišić’s indictment nor the

Prosecution evidence connected

General Perišić, with any de jure

political structures such as the

SDC, or de facto lines of

communication with any members of

the SDC, such as Dobrica Ćosić and

Zoran Lilić, two former Presidents

of the Federal Republic of

Yugoslavia who had been presiding

members of the SDC during the war in

Bosnia and Herzogovina, or with

Momir Bulatović and Slobodan

Milošević, two other voting members

of the SDC during the war in Bosnia

and Herzogovina.

The 2013 Appeals Chamber’s Judgment

determined that Perišić, who was

chief of staff of the VJ in the

critical period when crimes charged

in the indictment were committed in

Bosnia and Herzogovina, was

subordinated to then FRY President,

Zoran Lilić – who was never named a

member of a JCE nor was he indicted

at any court. The Judgment further

recounts that, although Perišić was

one of many individuals

participating at SDC meetings, the

final decisions were taken by the

President of the FRY, the President

of Serbia, and the President of

Montenegro.54

According to the Judgment, the

decision to provide VJ assistance to

the VRS was adopted by the SDC

before Perišić was appointed Chief

of the VJ General Staff in 1993.

This assistance – and its

consideration at SDC meetings he

attended – continued during

Perišić’s term of office with the

SDC reviewing both particular

requests for assistance and the

general policy of providing aid to

the VRS and the SVK. The Appeals

Chamber did find the VRS to be

linked to the crimes against

civilians but added that not all VRS

activities were criminal in nature.

The Appeal Chamber further

considered whether Perišić

implemented the SDC policy of

assisting the VRS war effort in a

manner that redirected aid towards

VRS crimes and decided that evidence

relating to General Perišić’s

contributions at meetings of the SDC

did not suggest that he advocated

specifically directing aid to

support VRS crimes, but that he

simply supported the SDC policy of

assisting the VRS.

The judgment, were it to survive

unchallenged, was immediately seen

around the world as favoring senior

military commanders. Critical

appraisals of the judgment expressed

concerns about significant changes

brought about by judicial precedent

concerning aiding-and-abetting

liability, which had previously

required proof of only two elements

to establish guilt. First, that the

accused knew that his conduct had a

substantial likelihood of aiding a

crime. Second, that the aid provided

had a substantial effect. The

Perišić judgment introduced a third

element, namely that the accused

must be proven to have “specifically

directed” the crime.55 The Perišić

Appeals Judgment was based on the

premise that the VRS – the Bosnian

Serb army commanded by Ratko Mladić

– were engaged in a legitimate

military effort and that Perišić was

aiding the legitimate war

activities, with no evidence that he

“specifically directed” the aid to

the commission of crimes.56

So what do acquittals actully mean

in legal terms? In the words of

former ICTY judge, Lord Iain Bonomy,

a court judgment of acquittal in a

criminal case does not rule that an

accused is "innocent".57 Judgments can

only determine whether an accused is

found guilty of the allegations

brought against him or her in the

indictment. The Prosecution must

prove these allegations beyond

“resonable doubt”.

Failing to rely on the JCE legal

doctrine, the Prosecution did not

even try to establish an evidentiary

connection between General Perišić

and the leaders of the RS, the RSK,

the FRY, and Serbia in articulating

a “common plan”. Perhaps if the OTP

had decided to indict all three

voting members of the SDC together

with Perišić and other high ranking

political and military non-voting

members, who attended the planning

meetings of the SDC, the course of

the trial, and the evidence, might

have resulted in a different

judgment.

Criminal cases can be won by a

combination of a sound legal theory

and persuasive trial evidence. The

prosecution and defence produce

evidence with the burden of proof

being on the prosecution. The last

word in evaluating the evidence when

rendering the judgment will have to

be the judges.

Power of States in Providing or

Obscuring Evidence

To what evidence do prosecutors and

judges have access? And what follows

from the reality that evidence in

high level cases will need to come

from the States that were involved

in the war? The ICTY experience

showed that not all relevant parties

engage in legal processes with

justice and truth in mind. There are

examples, at national and

international courts dealing with

mass atrocities, of outside

interventions by States aiming to

suppress evidence, to undermine

truth, and to create a

counter-narrative for various

reasons. States might act other than

in the genuine pursuit of justice,

even when they are compelled to

cooperate with international

criminal tribunals and courts to

open State archives, to make documentary

evidence available at trials, and to

facilitate access to witnesses by

the threat of United Nations or

European Union sanctions. If so, and

in order to avoid being sanctioned,

the States might engage in a subtle

play of appearing to cooperate,

while in reality trying – sometimes

with marked success – to keep

damaging evidence from a court and

from the public. There can be no

doubt that the cooperation of States

when it comes to the production of

evidence is of paramount importance

for the success and integrity of

mass atrocities trials.

Notwithstanding the huge amount of

audio, video, and written material

that exists about the Yugoslav

conflicts, ICTY prosecutors – unlike

their Nuremberg counterparts – did

not have full or easy access to

documentary material from the

archives of former leader

Milošević’s country.58 Documents from

the official archives of the FRY and

Serbia,59 considered more important

from a forensic point of view than

open source materials, were

difficult and sometimes impossible

to obtain. This was in stark

contrast to the experience of

prosecutors in Nuremberg, where

Allied Powers had simply seized the

State and Nazi Party archives of

defeated Germany for use as evidence

in court. Some of the most valuable

evidence for the trials of Serb

indictees, especially for high level

Serb political and military leaders,

was in the State archives of Serbia.

Milošević‘s trial was, to a degree,

a breakthrough for the ICTY in its

cooperation with Serbia. With

Milošević in custody in 2001 and the

trial about to start in 2002, the

ICTY turned to Belgrade for

evidence. The ICTY investigation

focused on evidence of Milošević’s

individual responsibility for using

armed forces in the campaign of

ethnic cleansing in the Serb

designated territories in Croatia

and Bosnia and Herzogovina.

Milošević was charged at the ICTY as

an individual with genocide in

Bosnia and Herzogovina, at

Srebrenica, and a number of other

municipalities. In parallel, Serbia

as a State was facing allegations

laid by Bosnia and Herzogovina in

1993 at the International Court of

Justice (ICJ) that it had breached

the 1951 Genocide Convention.60 It was

not only Milošević who stood trial

for criminal responsibility for the

crime of genocide, for at the ICJ a

Genocide Convention breach can only

be proved by first establishing the

commission of the relevant crime.

The extended fourteen years of ICJ

proceedings against Serbia were

running in parallel with the

Milošević trial at the ICTY for four

years, from 2002 to 2006. There was

a considerable “overlap” of evidence

needed to prove Milošević’s

culpability at the ICTY and evidence

needed to prove Serbia’s convention

breaches at the ICJ given that

Milošević was charged with genocide

at Srebrenica and six other BiH

municipalities.61 Milošević‘s trial was, to a degree,

a breakthrough for the ICTY in its

cooperation with Serbia. With

Milošević in custody in 2001 and the

trial about to start in 2002, the

ICTY turned to Belgrade for

evidence. The ICTY investigation

focused on evidence of Milošević’s

individual responsibility for using

armed forces in the campaign of

ethnic cleansing in the Serb

designated territories in Croatia

and Bosnia and Herzogovina.

Milošević was charged at the ICTY as

an individual with genocide in

Bosnia and Herzogovina, at

Srebrenica, and a number of other

municipalities. In parallel, Serbia

as a State was facing allegations

laid by Bosnia and Herzogovina in

1993 at the International Court of

Justice (ICJ) that it had breached

the 1951 Genocide Convention.60 It was

not only Milošević who stood trial

for criminal responsibility for the

crime of genocide, for at the ICJ a

Genocide Convention breach can only

be proved by first establishing the

commission of the relevant crime.

The extended fourteen years of ICJ

proceedings against Serbia were

running in parallel with the

Milošević trial at the ICTY for four

years, from 2002 to 2006. There was

a considerable “overlap” of evidence

needed to prove Milošević’s

culpability at the ICTY and evidence

needed to prove Serbia’s convention

breaches at the ICJ given that

Milošević was charged with genocide

at Srebrenica and six other BiH

municipalities.61

The ICTY prosecution investigators

found valuable evidence in the

collections of documents of three

important political bodies that had

powers to command armed forces: the

Presidency of The Socialist Federal

Republic of Yugoslavia (PSFRY –

Predsjedništvo SFRJ); the Supreme

Defense Council (SDC or VSO -

Vrhovni savet odbrane); and the

“Joint Command” (Zajednička komanda)

for Kosovo. These were the highest

State bodies in charge of commanding

the armed forces in the different

periods of the three wars: the

Presidency of SFRY was relevant for

the Croatian and Bosnia and

Herzogovina wars; the SDC for the

Croatian, Bosnia and Herzogovina,

and Kosovo wars; and the Joint

Command only for the Kosovo war.

Serbia's cooperation strategy in

relation to the ICTY focused on

keeping as much evidence as possible

in the Milošević trial from public

exposure if it was judged that it

could be of use to Bosnia and

Herzogovina in the ICJ proceedings.

Minister of Justice Nebojša Šarkić

of the FRY, “gave the game away” on

one occasion when explaining that

the release of the requested

documents would only “be possible

upon termination of disputes of FR

Yugoslavia with Bosnia and

Herzegovina and Croatia before the

International Court of Justice

(ICJ)”.62

The number of documents requested

but not received from Serbia grew

significantly in the course of 2002;

this prompted the Milošević

prosecution team to initiate in

December 2002 a procedure known as

“Rule 54 bis”, by which the Court

can issue orders to States for

production of documents. In the case

of unsatisfactory cooperation, the

ICTY Office of the Prosecutor (OTP)

- or a defense team if in a similar

position - could start the Rule 54

bis procedure, allowing the parties,

in theory, to obtain the documents

through a court order. In practice,

the process of acquiring relevant

evidence by a court order could take

months or years and, in some cases,

the requested evidence was never

handed over.63

But in the immediate post-Milošević

period, Serbia’s leadership appeared

to be less interested in meeting a

State obligation to cooperate with

the ICTY for the purpose of

rendering justice and establishing

truth than in instrumentalizing its

“cooperation” for a variety of

political goals: to fight political

opponents, to obtain international

financial aid, and to gain admission

to the European Union.64 But perhaps

the most important goal was to keep

evidence from the the International

Court of Justice (ICJ), because

evidence requested for the trial of

Slobodan Milošević by the ICTY could

also be used against the State of

Serbia at the ICJ.65

Serbia would cite numerous reasons

for noncompliance in their responses

to OTP requests, from disappearance

of documents during the NATO

bombardments of premises where they

had been stored to blunt denials of

their existence in the first place.

Serbia dragged out the process of

“cooperation” with long and

intensive negotiations with the

prosecution, sometimes succeeded by

direct “deals” with the Chief

Prosecutor to secure protection from

public view for the parts of the

high level records that were

selected as potentially damaging for

Serbia at the ICJ.

Obscuring Evidence Needed to Prove

Genocide

In February 2007 – less than one

year after Milošević’s death – the

ICJ rendered its judgment66 that the

crime of genocide in Bosnia and

Herzogovina did occur, but only in

1995 and only in the Srebrenica

area. It is important to note that

the 2007 ICJ judgment had been

rendered without the judges having

allowed themselves to review the

documents or the parts of documents

protected by the ICTY from public

view. Among these documents were the

records of the SDC, which were

protected from public view by the

ICTY at the request of Serbia.

Milošević’s de jure position during

the war in Bosnia and Herzogovina

was linked to his role on the SDC.

The SDC had been established as the

joint Commander-in-Chief of the FRY

armed forces by the 1992 FRY

Constitution and the SDC’s first

session was held in June 1992. It

was formed of the Presidents of the

FRY and the Republics of Serbia and

Montenegro; as President of Serbia,

Milošević was a member of the SDC

throughout the Bosnia and

Herzogovina war years. The records

of those high-level meetings

featured Milošević as a speaker on

policy issues and recorded his

precise words that captured his

state of mind before, during, and

after the conflict in which the Serb

forces committed atrocities in

Croatia, Bosnia and Herzogovina, and

Kosovo. These documents link

Milošević – and other members of the

SDC – to the Bosnian and Croatian

Serb leaderships during the 1990s

wars. They are useful evidence on

the de facto and de jure power of

Slobodan Milošević and the power

circles around him, exposing the

ways in which they schemed and

plotted together in order to

establish and re-draw Serbia’s

borders by force.67

Accidental Disclosure of Protected

Evidence

After the ICJ rendered judgment,

confirming the earlier ICTY

judgments,68 that the crime of

genocide in Bosnia and Herzogovina

did occur but only in 1995 and only

in the Srebrenica area, Serbia

seemed to have been able to

accomplish its goals as stated by

its officials on numerous occasions.69

But an unexpected development

followed, as some protection of the

selected portions of those documents

was lifted informally and without

court approval when Momir Bulatović

published a book, Unspoken Defence,

in which he quoted from protected

portions of a number of SDC

transcripts.70 However, the ICTY made

no efforts to challenge or amend the

original decisions on protection or

to sanction Bulatović. Bulatović’s

book would have been ignored by the

public if it were not for an article

published by International War and

Peace Reporting (IWPR) in November

2007. The author of the article

wondered how it was possible that

neither the team who presented the

Bosnian genocide case before the ICJ

nor the ICTY Prosecution team had

used Bulatović’s publication of some

of the protected parts to initiate

legal proceedings to lift the

protections.71 The November 2007 IWPR

publication might have been used as

a trigger for the Bosnian legal team

to start the process of a revision

of the ICJ judgment rendered in

February 2007 and for which an

application for “revision” could,

under the ICJ statute, be made in

the following decade until February

2017, not beyond; but it did not

happen. It also did not happen in

2011, four years later, when the

ICTY made available to the public

the majority of the protected

portions of the SDC documents, which

were released from their protection72

in the trial of General Momčilo

Perišić, the Chief of Staff of the

VJ from 1993 to 1998.73 But, after

much publicity, the Appeals Chamber

in the Perišić case did not

apparently find these documents

persuasive enough as he was

acquitted.

As it is now – with Perišić not

tried for genocide at all and

acquitted, Milošević dead, and other

SDC members never indicted – the

historical record leaves the FRY and

Serbia free to say they were nothing

but observers of the tragedies

taking place in the neighboring

States of Bosnia and Herzogovina and

of Croatia. Many would argue that

this is a travesty of the truth.

Moreover, by deadline in February

2017 Bosnia and Herzogovina failed

to file a revision at the ICTY.74 With

the ten years period of limitation

expired, there will be no legal

remedy even if and when the most

compelling evidence becomes

accessible to the public.

For historical narrative, the 2013

Perišić Judgement and the 2007 ICJ

judgment devalued the legal

importance of the SDC records. None

of the legal procedures dealing with

the SDC records sufficiently

stressed to the outside audience

that those redacted pages finally

available did not tell the full

story. The majority of the SDC

records for 1995 – the year that

Srebrenica genocide took place –

have never been handed over and are

still missing. Once

they appear by chance or by

deliberate search in the future,

historians might have the last word

in reconstructing of sequence of the

events and decisions that had led to

genocide. This is where historians

may take the lead and continue

filling the gaps and answering the

open questions about the individual

responsibility of the Serb

politicians and military, as well as

of Serbia as the State, for the

crimes of genocide that occured in

Bosnia and Herzogovina from 1992 to

1995.

AN UNFINISHED MASS ATROCITIES TRIAL

AND ITS

EXTRALEGAL VALUE

All ICTY trial archives represent

valuable historical sources because

they contain an immense, unique

collection of documentary evidence,

testimonies, and legal documents.

Materials selected as evidence by

the prosecution and defence

incorporate documents from Yugoslav,

Serbian, Kosovo, and Bosnian State

archives that would have otherwise

been unavailable to the public and

to researchers for many decades.

The Milošević trial – although

unfinished – serves as a valuable

historical source for at least two

reasons. First, Milošević

represented himself in court, and

therefore responded personally to

the evidence presented, but also

made personal remarks throughout the

trial from the standpoint of a man

attempting to defend his political

and private decisions. Second,

evidence that did come directly from

State archives in Serbia makes the

Milošević trial record particularly

valuable, as it includes State

documents that would otherwise have

remained protected for decades or

even longer.

The Milošević trial archive

comprises transcripts, material

tendered as evidence, motions on

administrative and procedural

matters, and decisions and judgments

of the Trial Chamber and Appeals

Chamber. The archive is so large

that it is too substantial to be

analyzed in a single study.

Nonetheless, missing source

materials – such as the critical

1995 SDC records – that were

requested but never produced

represent a gap; meaning that the

trial record, while vast, is not

comprehensive or exhaustive. Despite

its size, a trial record alone might

be insufficient for the task of

historical research, and sources

from outside the trial proceedings –

such as theoretical and historical

academic writings and so called

“extratrial material”75 – will be used

by historians. The Milošević trial archive

comprises transcripts, material

tendered as evidence, motions on

administrative and procedural

matters, and decisions and judgments

of the Trial Chamber and Appeals

Chamber. The archive is so large

that it is too substantial to be

analyzed in a single study.

Nonetheless, missing source

materials – such as the critical

1995 SDC records – that were

requested but never produced

represent a gap; meaning that the

trial record, while vast, is not

comprehensive or exhaustive. Despite

its size, a trial record alone might

be insufficient for the task of

historical research, and sources

from outside the trial proceedings –

such as theoretical and historical

academic writings and so called

“extratrial material”75 – will be used

by historians.

MASS ATROCITIES TRIAL AS A

HISTORICAL SOURCE

The historical record of this trial

due to its size will remain an

amorphous mass if not filtered by

relevance accorded thereto by a

researcher. This is why a historical

record might be best exploited when

specific transcripts, documents, or

videos are selected for their value

as a historcal source.

Marrus made a valid point that the

trial archive of any mass atrocities

trial should be treated just as any

other historical source. He

emphasized that historians must

evaluate every source with an eye to its

provenance, because all sources are

in some sense “tainted”, and war

crimes trial records are certainly

no exception.76 Using a trial archive

as a historical source can influence

historical narrative, but not in the

sense that there will ever be one

uncontested historical narrative.

Evidentiary focus of criminal

proceedings might unwittingly

influence historical interpretation

and create what has come to be

known, because the Holocaust trials

in Nuremberg, as an “intentionalist”

view of the historical period in

question. Thus reliance on the

Nuremberg trials archives has led

historians to maintain that the

Holocaust resulted from an explicit

master plan created by Adolf Hitler

himself and implemented top-down.77

Only later was attention directed to

the role of minor bureaucrats and

functionaries at all levels of

German society – an approach that

yielded a “functionalist”

interpretation focused on the

complicity of ordinary Germans in

the Holocaust, to such an extent

that some scholars now ascribe the

adoption of the Final Solution

primarily to social and political

pressures working their way

bottom-up.78

So did the Milošević trial archive

contribute to the already existing

historical narratives? The part

Milošević played in events of the

1980s and 1990s has been explored in

a number of political biographies.

The best known of these biographies,

written in both English and Serbian,

were published before his trial or

in the same year that it started.79

This means that only few authors

presented the trail of evidence that

was followed in the courtroom to

establish responsibility for the

break-up of Yugoslavia and, more

importantly, the violence that

followed.

A majority of authors agree that

Milošević played a central role in

events that unfolded in the former

SFRY between 1987 and 1999. There

are at least three categories of

interpretations of Milošević’s role

in the disintegration of Yugoslavia

that could be identified so far:

intentionalist, relativist, and

apologist. “Intentionalists” see

Milošević as having dictated the

pace of the Yugoslav crisis through

well-articulated and planned

objectives that drove the other

republics away. According to this

view, violence was used cynically

and practically with a clear

purpose.80

Alternative to this are authors who

tend to see Milošević as an

intelligent and ruthless politician

but not a good tactician or

strategist, whose politics were

mostly reactive.81 These “relativists”

see Milošević’s policies as

responses to developments that

were driven by leaders of Slovenia,

Croatia, Bosnia and Herzogovina, and

Kosovo, and by the international

community. From this standpoint,

Milošević genuinely wanted to

preserve Yugoslavia but did not

succeed.82 Relativists perceive

Milošević as an ambitious politician

who endeavored to achieve more than

he was capable of; and his rule has

been cast by authors in this camp as

a sequence of mistakes and failures

– at the national and international

levels.83 The violence that

accompanied the disintegration of

Yugoslavia is thus explained as

resulting from a complicated

interplay of many factors, leading

to an escalation of the crisis that

was beyond the control of Milošević

alone.

“Apologists” share the opinion held

by relativists regarding the role of

the republics that sought

independence and of the

international community in the

disintegration of Yugoslavia. Yet

they not only see his goal to

preserve Yugoslavia as

well-intentioned but also defend his

politics and decision-making in

general.84 They downplay Milošević’s

calculating and ruthless side to

recast him as a clumsy, wayward, and

inconsistent authoritarian leader

who merely failed to deliver on

promises he made.85

With Milošević dead and his trial

archive left behind to be studied,

there is no doubt that most of the

prosecution evidence would support,

as a rule, an “intentionalist”

interpretation of the history and

that evidence of the defense, an

“apologetic” or “relativist”

interpretation. It may be

unrealistic to expect that mass

atrocities trials could ever produce

one uncontested historical narrative

and one shared collective memory. In

reality, a plurality of narratives

seems more probable, more

democratic, and maybe more desirable

than one overall narrative. Over the

course of time, the historical

narrative most certainly will

develop and change with the

emergence of new sources and with

new theoretical insights long after

a trial ends.

CONCLUSIONS

Mass atrocities

trials – just as any other criminal

trials – are there to render justice

and mete out punishment. The ICTY

examples show that justice can be

interpreted and perceived in many

different ways. It is almost

impossible to identify any ICTY

judgment and a sentence delivered in

the last twenty years that was

greeted with approval by all sides

involved in the Yugoslav wars. Every

judgment – conviction, judgments on

pleas of guilty, or acquittal – has

led to divisive and often emotional

reactions of those who found the

judgments either too lenient or too

harsh; the trials unfair,

non-transparent, or

incomprehensible; and the courts

politicized.

And some of these

criticisms, however expressed, may

not be completely unfair or without

foundation. It is obviously

impossible for mass-atrocities

trials to produce the “real truth”

or some form of uncontested

historical narrative(s), not least

because the procedural restrictions

inherent in such trials that are

bound to limit their ability to

record a completely accurate

history. There are limitations of

jurisdiction, limitations of the

adversarial legal system generally

coupled with restrictive rules of

adversarial systems on the

admissibility of evidence.

Prosecutorial discretion about whom

to indict, for which crimes, and for

which charges adds to those

limitations as may confidentially

obtained (and thus secret)

protection of some evidence from

public view. Plea agreements between

the accused and the prosecution when

defendants plead guilty can narrow

public knowledge of the real gravity

of the crimes committed in some

geographical area or by some

military unit or controlling

political body; the public

assumption will be that the

agreement reflects what actually

happened whereas it may have been

made to save time or because some

evidence was weak and the

prosecution were never certain of

getting convictions – or for other

reasons.

Will judges and

lawyers have the last word when it

comes to the establishing of a

dominant or uncontested historical

narrative? Not likely, although when

judges produce careful balanced

judgments on properly presented

evidence, their analysis and

judgments may be of far greater

value than some single piece of

evidence deployed by polemicist,

politician, or historian.

Accordingly, the

historical record left by such

courts may be vast but is bound to

be incomplete. This fact must never

be sidestepped out of enthusiasm for

some court judgments favorable to a

particular cause; nor should it

allow the immense part that court

records can play in setting

historical narratives be diminished.

And even this recognition does not

capture all the caution with which

we should consider trial records.

The fact that

international criminal trials focus

on the criminal responsibility of

individuals for mass atrocities

raises the question of whether it

should be only individuals who

should bear the burden of criminal

accountability for what may have

been State violence committed over a

long period of time through the

agency of institutional structures.

Selecting a relatively small number

of individuals to prosecute for

crimes that occurred over a

protracted period of time – as has

been the case since the

establishment of the international

criminal courts and tribunals from

1993 onwards – can lead to

historical “simplification”, where

too much focus on an individual can

overshadow the long-standing

historical processes that have led

to the commission of mass

atrocities.

In addition to

these proper restrictions inherent

to the ways mass atrocities trials

operate, it is necessary to be

realistic about the power that

States will exercise to control

evidence when they fear for their

their national interest – whether or

not those fears should be respected

as a matter of law. What States have

done, and may continue to do, can be

seen as improper; but it should be

remembered that it is not entirely

dissimilar from what defense lawyers

can properly do when they know of or

have in their possession but do not

produce in court evidence that is

perceived as adverse to their

client.

With all these

conclusions in mind, the most

profound difference between legal

and historical narratives is that

the legal narrative as captured in

trial transcripts, evidence, or in

judgments will remain frozen in

time. If new evidence emerges that

allows re-opening the trial or a

re-trial, it has to happen while a

defendant is alive. After a

defendant dies, new evidence that

might emerge will be left to

historians to record, evaluate and

judge.

|