|

Case

study 2

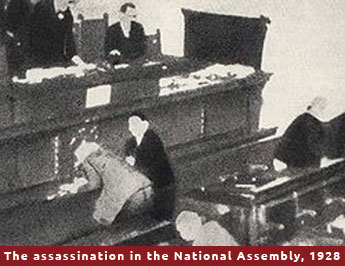

The first decade

in the life of the Kingdom of Serbs,

Croats and Slovenians ended in

bloodshed: on June 20, 1928

Radicals’ MP of the parliamentary

majority Puriša Račić gunned down

two MPs of the Croatian Peasant

Party /HSS/ (Dr. Đuro Basariček and

Pavle Radić), wounded two (Dr. Ivan

Pernar and Josip Granđa), while the

fifth, the party leader (Stjepan

Radić) succumbed to his wounds a few

days later. Four out of the five

were in the leadership of HSS (the

Croatian Republican Peasant Party

till 1925) the indisputable

political representative of the

Croat people on the account of

parliamentary seats won in all

earlier elections. The consequences

of the shooting were both immediate

and far-reaching. The former became

evident in almost no time:

pseudo-parliamentarianism collapsed

to be replaced by overt dictatorship

of King Alexander (January 6, 1929).

Reactions to the crime, especially

by foreign press, hinted at the

latter. By the way the crime was

committed in – the way that must

have humiliated the entire Croat

nation – foreign commentators only

logically predicted new tensions in

the Kingdom.1

Historiographic

writings in various centers of the

Kindgom and, later on, of the

Republic of Yugoslavia have not

ignored the factographic side of the

crime the scene of which was the

People’s Assembly. And yet, Croatian

authors were those who occupied

themselves with it the most.2 Many of

them were publishing integrally the

transcripts taken at the People’s

Assembly’s sessions discussing the

crime as prime historical source.3

Some were explaining they were doing

it “to venerate the memory of the

victims.”4 True, no interpretation

could replace the authenticity of

the above-mentioned transcripts. But

by quoting only, these historians

were freeing themselves of the

obligation to discern the motive

from the long history of crime, from

its essence.

The WWII when so

much to what the Kindgom’s instable

peace had paved the way to,

subsequent rebuilding of Yugoslavia

and the new order placed in the back

seat not only the interest in the

bloodshed in the People’s Assembly

but in the Kindgom itself. However,

conditions for the renewal of that

interest were being created in

1960th and 1970th. Historical

distance was there, and

contemporaries of the events

silenced by circumstances up to then

were still alive. Many had written

memoires while in emigration and

began publishing them (V. Maček, I.

Meštrović, S. Pribićević, M.

Stojadinović, etc.). However,

crucial was the renewal of “old”

controversies, especially about the

character of the common state, a

deep-rooted controversy considering

constant constitutional amendements.

Feeling freer to research historians

began turning their attention to the

causality of the events from recent

and not so recent past. And so the

turn came to the bloodshed in the

People’s Assembly: the incident that

had lethally spurred “separatist

currents, especially at the time of

Yugoslavia’s occupation in

1941–1945.“ And so the context came

under scrutiny. “Račić’s shooting,

resulting from the unsettled

controversies permeating the entire

public sphere of old Yugoslavia at

the time, was a culmination of

political tensions and conflicts

between the official centralism and

oppositionist anti-centralism.”5 The WWII when so

much to what the Kindgom’s instable

peace had paved the way to,

subsequent rebuilding of Yugoslavia

and the new order placed in the back

seat not only the interest in the

bloodshed in the People’s Assembly

but in the Kindgom itself. However,

conditions for the renewal of that

interest were being created in

1960th and 1970th. Historical

distance was there, and

contemporaries of the events

silenced by circumstances up to then

were still alive. Many had written

memoires while in emigration and

began publishing them (V. Maček, I.

Meštrović, S. Pribićević, M.

Stojadinović, etc.). However,

crucial was the renewal of “old”

controversies, especially about the

character of the common state, a

deep-rooted controversy considering

constant constitutional amendements.

Feeling freer to research historians

began turning their attention to the

causality of the events from recent

and not so recent past. And so the

turn came to the bloodshed in the

People’s Assembly: the incident that

had lethally spurred “separatist

currents, especially at the time of

Yugoslavia’s occupation in

1941–1945.“ And so the context came

under scrutiny. “Račić’s shooting,

resulting from the unsettled

controversies permeating the entire

public sphere of old Yugoslavia at

the time, was a culmination of

political tensions and conflicts

between the official centralism and

oppositionist anti-centralism.”5

A study of the

incident itself, detailed inansumuch

as scrupulous, belongs to the period

of grown interest in the bloodshed

taking place in the People’s

Assembly.6 It is the more so worthy

as its author has found witnesses

and gave them floor. The latter were

very old, “with one foot in the

grave,” and the historian was by far

more interested in their reflections

about complexities of Yugoslavia’s

history and their causality than in

details witnesses remembered. These

reflections were not a fruit of some

historical theory but of human

desire for truth and justice

knowledge can help to reach.7

The ideal way to

come to historical explanation of

the crime committed in the People’s

Assembly on June 20, 1928 is

comparable to exploring with a probe

the insides of the entire state and

society, the structure of their

mentality and political culture; and

the illegal sphere with its secret

organizations such as King

Alexander’s “White Hand” /Bela Ruka/

in the Army.8

Despite all the

difficulties of exploration

comparable to a probe, unmistakable

dots remain in full view and, once

connected into a single line, lead

towards a relevant conclusion about

the causes and consequences of the

crime. It is a historian’s duty to

draw that line. This is why quoting

authentic historical sources such as

transcripts taken in the People’s

Assembly are not good enough.

St. Vitus Day Constitution declared;

political tensions grow;

attempt at reaching compromise; the

strategy changed

Declaration of the

St. Vitus Day Constitution failed to

relax the situation in the country.

On the contrary, the gap between

centralists and anti-centralists

grew deeper and deeper. Stjepan

Radić announced he recognized not

the Constitution and not without a

good reason. Four of Croatia’s

parties formed the Croatian bloc

that had the support of the majority

of Croat population. Declaration of the

St. Vitus Day Constitution failed to

relax the situation in the country.

On the contrary, the gap between

centralists and anti-centralists

grew deeper and deeper. Stjepan

Radić announced he recognized not

the Constitution and not without a

good reason. Four of Croatia’s

parties formed the Croatian bloc

that had the support of the majority

of Croat population.

Soon after the

Constitution was declared in

Belgrade (August 10, 1921) King

Peter I died. The Zagreb

municipality refused to send a

delegation to his funeral; and the

government, therefore, dismissed its

management. Stjepan Radić was

elected the prefect in the elections

that ensued – a testimony of HRSS’s

repute not only in the countryside

but in the city as well. And yet,

the trench warfare was not over: the

government sent its commissioner to

Zagreb.

To draw Europe’s

attention to the “Croatian question”

the Croat bloc addressed a

memorandum to the International

Conference in Genoa.9 The entire

Kingdom was in turmoil. In late 1922

the Radical Party formed the

government. As early as in March

that followed it called the

elections for August 18, 1923.

During the election campaign the

Radical Party was settling accounts

with the Democratic Party accusing

the latter of its readiness to reach

an agreement with Croats.

HRSS triumphed in

the elections but continued

boycotting the People’s Assembly.

How to overcome the impasse? HRSS

and the Democratic Party were trying

to find a way out. Initiated by HRSS

the talks with the Radicals were

first held in Belgrade (in early

April 1924) and then in Zagreb. They

resulted in the Zagreb or Marko’s

protocol10 that paved the way to the

agreement. But the Radicals treated

the document like they had the Corfu

Declaration: that is no agreement at

all, they claimed, but just a memo.

In a public address (June 7, 1923)

Pašić started distancing himself

from it.

Embittered by

Pašić’s disloyalty, Radić told the

HRSS convention commemorating the

anniversary of the French Revolution

(July 14, 1924) that Croatia was a

prisoner of “the Serbian Bastille.”

Another of his statements was seen

as an insult to the King and the

Queen. The procedure for depriving

him of MP immunity and putting to

trial was launched. To avoid such a

scenario and with a helping hand

from his associates Radić went

abroad undercover. From Vienna he

made towards Paris and London

advocating with European governments

for the “Croatian question.” His

mission failed: his interlocutors

were only interested in stability of

the Balkans and the East

Mediterranean. In other words, they

were concerned with the survival of

the Kingdom of SHS at any price,

including Serbia’s domination over

smaller nations making it.

During his tour of

Europe Radić was invited by Soviet

Foreign Minister G.V. Chicherin to

visit Moscow. Once there, he

enrolled his party in the membership

of the Peasant International, a part

of the Third International

(Komintern). At home, the news about

it was seen as high treason.

A year later Radić

returned to the country. He was

arrested on January 5, 1925. He was

charged with a crime punisheable

with ten-year imprisonment and a ban

on his party. And then, strategies

were changed: both by

anti-centralists and centralists.

Elections were

called for February 8, 1925. HRSS

won 67 seats, while Stjepan Radić

triumphed in three electoral

districts though from prison. And

against the background of high

tensions he decided to take yet

another risky step that was

subsequently labeled capitulation, a

political maneuver or a new

strategy. In the People’s Assembly

(March 27, 1925) his nephew Pavle

Radić, the HRSS politician people

trusted the most, read out a

statement by his party’s leadership

– the statement that rounds off the

period from 1918 to 1925. Elections were

called for February 8, 1925. HRSS

won 67 seats, while Stjepan Radić

triumphed in three electoral

districts though from prison. And

against the background of high

tensions he decided to take yet

another risky step that was

subsequently labeled capitulation, a

political maneuver or a new

strategy. In the People’s Assembly

(March 27, 1925) his nephew Pavle

Radić, the HRSS politician people

trusted the most, read out a

statement by his party’s leadership

– the statement that rounds off the

period from 1918 to 1925.

Writings about the

history of the Kingdom of SHS

usually quote the passage of the

statement that, at the time, turned

the wheel of history:

“We acknowledge

the overall political situation as

it is today by the St. Vitus Day

Constitution and with the

Karađorđević dynasty at the throne.”11

However, the

statement has many meanings.

Pragmatic as it was, though not out

of fear or in the attempt to have

his leader released from prison,

HRSS – or HSS – practically set the

foundation for its activity in the

times to come:

“We want to be

politically equal, like Croats,

Serbs and Slovenians are, being

three equal brothers. If we make up

the same people, we hear them

saying, it makes no difference

whether a Serb or a Croat is in some

office, and then, when all the

offices are occupied by Serbs, again

we hear them saying, it’s all the

same.

“If in this

country, it’s not all the same to

us. We do not want to be here

quantité négligeable (the quantity

that can be neglected). We want our

share here, we want to be among the

creators of this state…We want to be

equal in decision-making since our

people, thank Heaven, are

politically too mature to be treated

as second rate citizens or to have a

status as such…”12

Recognizing the

factual state of affairs – the St.

Vitus Day Constitution – the

statement quotes at the same time,

“To amend these facts and the state

of affairs our will and conscience

cannot possibly approve of, the

Constitution, the said popular

agreement between Serbian, Croat and

Slovenian peoples should be

revised.”13

Was the Court

really sure that it has finally

subjugated Croats? It continued

putting them to the test by

appointing them ministers, Stjepan

Radić included. As for Radić, he

turned to the struggle against

corruption the center of which was

the Court. “The people in the King’s

circle belong more behind the bars

than in the Court.”14 With a policy as

such Radić was finding an echo among

the peasantry in Serbia and

Macedonia. And that was threatening

indeed; his activism triggered off

the idea about his liquidation, the

more so after he formed, with his

once opponent Svetozar Pribićević,

the Peasant Democratic Coalition.

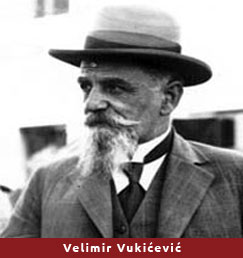

Last elections

before January 6 Dictatorship were

held on September 11, 1927. The

already quoted Dragoljub Jovanović

compared the country to a mental

asylum. And it was in 1928, at the

time of Velja Vukićević’s

premiership, that the idea about

Radić’s liquidation – born in Serbia

earlier15 - became “legitimate.”

Vukićević, the secondary school

teacher with no political authority

and reputation, was King Alexander’s

man. In his newspaper “Jedinstvo”

/Unity/ he was openly calling for

the murder of Stjepan Radić.

Assassination of Stjepan Radić and

his associates prepared

Preparations for

for the murder of Stjepan Radić and

his associates in the People’s

Assembly on June 20, 1928 (a precise

gun was procured, Stjepan Radić

himself prevented from attending a

conference of the Interparliamentary

Union so as to ensure his presence

in Belgrade on June 20; and sessions

of the parliament were chaired

contrary to the relevant procedure

Dr. Ninko Perić, the chair and law

professor, must have been well aware

of) have been examined in detail in

Croatia’s historiography.16 This leads

to the conclusion other historians

share with their Croat colleagues

that the assassination had been

contracted and organized, executed

impassively and in cold blood, while

executioners felt safe. The

executioners were known, the small

circle of their accomplices, too. As

for those who ordered it, all the

leads pointed toward the Court – or

to King Alexander. But like in all

political murders demonstrative

evidence was missing for the simple

reason that such traces are never

left behind.

The atmosphere

creating psychological and political

climate for the murder was examined

in particular detail – the manner in

which the public in Serbia had been

prepared for all earlier political

murders.17 The word already had it.

People in many places were telling

one another, “Radić is killed!” Then

the very term murder became

frequent. With his anti-Yugoslav

editorial policy Milan Gavrilović,

the editor-in-chief of the Politika

daily, was brewing bad blood between

Serbs and Croats. And “Jedinstvo,”

the above-mentioned mouthpiece of

Prime Minister Velja Vukićević, who

was financing it from disposition

funds under his control, was openly

threatening the leaders of the

Peasant Democratic Coalition Stjepan

Radić and Svetozar Pribićević with

murder. The atmosphere

creating psychological and political

climate for the murder was examined

in particular detail – the manner in

which the public in Serbia had been

prepared for all earlier political

murders.17 The word already had it.

People in many places were telling

one another, “Radić is killed!” Then

the very term murder became

frequent. With his anti-Yugoslav

editorial policy Milan Gavrilović,

the editor-in-chief of the Politika

daily, was brewing bad blood between

Serbs and Croats. And “Jedinstvo,”

the above-mentioned mouthpiece of

Prime Minister Velja Vukićević, who

was financing it from disposition

funds under his control, was openly

threatening the leaders of the

Peasant Democratic Coalition Stjepan

Radić and Svetozar Pribićević with

murder.

The paper’s

insolence was also to be ascribed to

the trap the cabinet found itself

in. The parliament had the Neptune

Conventions with Italy on agenda.

The Conventions were not in the

country’s interests in Dalmatia,

Croatian Coastland and islands.

Croats were especially embittered by

them. In Belgrade (May 31, 1928)

people were protesting under the

slogans, “Down with fascism!” “Down

with Mussolini!” “Long live

Dalmatia!” and “Long live the

Yugoslav Rijeka!” Gendarmes

intervened brutally hurting a number

of citizens. The opposition called

for a parliamentary debate on the

incident and the cabinet’s

resignation.

Two weeks before

the bloodshed in the People’s

Assembly (June 14, 1928) Vukićević’s

paper run a story under a banner

saying, “One can speak with swines

only in their own language!” Its

author announced, “Traitors’ and

wicked persons’ heads will be

chopped off if need be to have peace

and order in the country and the

parliament with authority.” And he

also quoted a passage from a letter

he wrote Col. Pavle Juzbašić (1922),

“It is your paramount duty then to

kill Svetozar Pribićević in Belgrade

and Stjepan Radić in Zagreb.” The

other side answered the fire. So,

Radić’s paper “Narodni Val”

/People’s Wave/ wrote (June 16,

1928), “Only Balkan bandits can

write like this…”

Many Radicals’ MPs

were also aware of the impeding

catastrophe. Having been warned by

them, Radić, only 22 hours before

assassination, dictated by phone a

story titled “Velja Vukićević’s

Diabolic Plan” to be published in

his Zagreb-based paper.

“A Radicals’

leader, MP and ex-minister told me

by phone that Velja Vukićević was so

furious that he would refrain from

nothing. This also means that would

stop at nothing to stay in power.

And that’s why what his paper

Jedinstvo published – that Radić and

Pribićević should be killed – is not

just a mere threat. Not a single

situation so far has been so

barbarious and so contrary to all

the notions of political and

parliamentary struggle as this one

(emphasis by L.P.). And that’s why

some Radicals’ leaders decided to

publicly oppose all this in the

parliament…”

Shots fired in the People’s Assembly

Having been

promoted by the press and the rumor

discrediting Radić, the idea about

the murder had the front door to the

parliament wide open to it. On the

eve of the bloodshed (June 19, 1928)

a group of 23 MPs led by Puniša

Račić put forward the motion for

having Stjepan Radić medically

examined given that his actions

“cause strong and justified doubts

about his being a normal person.”

They wanted, they explained, to

avoid possible developments.18 And on

the day of assassination MPs were

telling each other, “Radić will be

killed today.” Commenting on the

ensuing parliamentary debates, many

historians simply concluded that the

Assembly resembled “a Balkan pub.”

These debates were registered in

detail the Assembly’s transcripts

and in the then press. Even years

later historians were impressed by

their vehemence that overshadowed

political essence. Harsh words were

uttered in the name of a policy and,

it could be said, in the name of an

already criminalized whose promoters

had been defending the interests of

a camarilla while invoking the

nation and its best interests. In

any case, the atmosphere on the eve

of the assassination was such that

Radić’s associates and friends were

trying to dissuading him from

attending the session next day. He

went, nevertheless, and silently

listened to the debate. And it was

his life that was at stake.

Addressing

Croatian MPs, Radical from Kosovo

Toma Popović said, “If your leader

Stjepan Radić, an embarrassment to

the Croatian nation, goes on with

his insults, I can guarantee…that

Serbia will not be to blame, that

Serbs will not be to blame, but you,

who have not been trained. It’s a

shame to have you, as you are, in

the People’s Assembly.” (The

opposition goes on shouting,

protesting and banging against

benches.).19

Puniša Račić just

waited for a reason why to act, and

it came with a remark made by Dr.

Ivan Premer he might have not –

eyewitnesses are not quite sure

about it – heard properly and even

less understood. Before starting to

shoot, he said from the rostrum: Puniša Račić just

waited for a reason why to act, and

it came with a remark made by Dr.

Ivan Premer he might have not –

eyewitnesses are not quite sure

about it – heard properly and even

less understood. Before starting to

shoot, he said from the rostrum:

“Ever since I’ve

begun socializing, ever since I’ve

become a man (laughter), I’ve never,

not for a single moment, overlooked

the interests of the Serbian people,

the interests of my homeland.

“I declare before

you all that Serbian interests –

whenever guns and cannons are not

firing – were not more engangered

than today (clamor). And, gentlemen,

when as a Serb and MP I see that my

nation and my homeland are in

jeopardy, I say loud and clear that

I will use some other arms to

protect the interests of Serbhood.

“Our country

should have consolidated itself

several years ago, our people should

have profited from what they

attained in the war with bravery

(emphasis – L.P.) and fidelity to

its allies, while, what’s worst of

all, a part of our people was using

slander to undermine consolidation

and betray the interests of our

people and this country of ours.”20

At this point, Dr.

Ivan Perner interrupted him with a

rather meaningless remark, “You have

robbed beys.” Račić demanded his

punishment from the chair of the

People’s Assembly, or else “I will

punish him myself,” he said. He

threatened all MPs, “Whoever tries

to intervene between me and Perner

will be killed.” And he fired at

Perner. The Chair of the People’s

Assembly just said, “The session is

being adjourned.” Stenographers

noted down, “The session was

adjourned at 11:20 a.m.”21 Here the

transcript ends.

Puniša Račić went

on firing his gun. Dr. Đuro

Basariček was shot dead. Pavle Radić

died in hospital. Josip Granđa who

tried to protect him was wounded: he

died on August 1928 in Zagreb.

Historians have debated whether

Puniša Račić was aiming carefully or

shooting at random. Be it as it may,

Stjepan Radić was his target.

On the basis of

transcripts and reports by its

journalists attending the session,

the Politika daily dedicated almost

an entire issue (June 21, 1928) to

this “historical session.” And then

went on for days to write about the

crime. There were hints at the

murder’s “insanity.” The paper ran a

story about King Alexander visiting

the wounded Radić in the hospital.

Their conversation, according to the

paper, was as follows: the King – “I

came to see you.” Radić – “Thank

you, thank you very much!” and then

he kissed his hand. However, judging

by the statement for the court he

gave 14 days before he died, Radić

told the truth as he saw it: “All in

all, I am convinced that Puniša

Račić was just an executioner of

what had been planned and agreed on

by a part of Radicals’ caucus, and

probably with the knowledge and

maybe the approval of parliamentary

chair Dr. Ninko Perić and Prime

Minister Velja Vukićević.“22 Radić’s

statement led to Minister of the

Court Dragomir Janković and its

highest noblemen. Croatia was imbued

with this feeling. Three hundred

thousand people attended his

funeral, and this mass attendance

“had the significance of a strong,

anti-Serb, anti-governmental and

anti-regime manifestation.”23

After assassination: the hero left

down and the murdered privileged

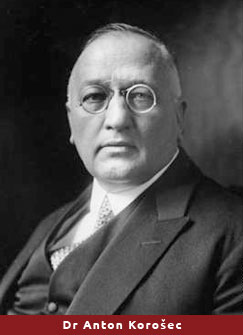

Having committed

the murder, Puniša Račić passed

through ministerial chambers onto

the street exclaiming, “Long live

Serbia, long live Greater Serbia!”

His friend Dragomir Bojović, the

accomplice, had been waiting for him

in a car. Where he had stayed before

giving himself up remains

disputable: was it in some apartment

or in a military facility. In the

afternoon he went to see Minister of

the Interior Anton Korošec. Refusing

to receive him as he was not an

executive officer, Korošec had him

sent to the City Hall. Having committed

the murder, Puniša Račić passed

through ministerial chambers onto

the street exclaiming, “Long live

Serbia, long live Greater Serbia!”

His friend Dragomir Bojović, the

accomplice, had been waiting for him

in a car. Where he had stayed before

giving himself up remains

disputable: was it in some apartment

or in a military facility. In the

afternoon he went to see Minister of

the Interior Anton Korošec. Refusing

to receive him as he was not an

executive officer, Korošec had him

sent to the City Hall.

Puniša Račić was

self-confident: he did not realize

that he was nothing but an

instrument of the crime.

Belgrade-seated „Reč“/Word/paper

described (June 23, 1928h) how first

meeting with reporters, with him

already in jail, looked like.

“A coached

stopped… Puniša came out and nobody

would say he looked like a murderer.

Puniša stepped out, clean shaven, in

brand new, lilac suit, with a new

straw hat on his head and wearing

brown shoes. Not a trace of

anxiousness. When he saw

photographers about to take his

picture, he addressed them smiling,

‘Wait till I stand still and then

take a shot.’ And he stepped at the

first flight of stairs and looked

into the camera peacefully and with

a smile. Everyone was surprised by

the murder’s looks, everybody having

expected to see him brought in

handcuffed.”

Račić felt assured

that his mission had been grand. Why

shouldn’t he when he had been

supported by the circle closest to

the Court, his party, the

parliamentary chair and the Prime

Minister? He was looking forward to

recognition and glory. And then he

turned out to be just a murderer

under protection. His trial was a

farce. Contrary to the law, the

Minister of Justice appointed the

investigative judge. This

predetermined the course of the

proceedings. This was why most of

Belgrade’s lawyers refused to

represent the defense. Stjepan

Radić’s family and party boycotted

the process. The attempt to engage

some French lawyers failed. And it

was the US charge d’affaires in

Belgrade who poked a “probe” into

the process – or in the mentality

and political culture. He wrote in

his report to the Secretary of State

(June 15, 1929):

“To an observer

from the West the way in which this

trial is being handled is

disgusting. Using a less harsh term

would be hard indeed, since all the

motions, from the beginning to the

end, have been marked by deficiency

of dignity for which the President

of the court is responsible beyond

any doubt, and which was often

ridiculed and made a laughing-stock

by both the accused and the audience

of some twenty-odd lawyers and about

the same number of reporters. So,

when a Serb MP was describing

jokingly how his colleagues (but not

him) had rushed to hide themselves

under benches the moment the

shooting started, the audience was

cheering openly at such

inappropriate remarks.”

The American

diplomat goes on, “It is sad to note

that in a case like this one the

murder himself, Račić, was pushy and

manifested no remorse throught the

trial, since he, shooting off his

mouth, took up the role of a patriot

attacked by rebellious elements who

were allegedly after his personal

honor. It is even sadder to note

that several Serbian MPs and one

ex-minister tried to justify the

murder’s act by saying Račić had

acted in self-defense…There can be

no doubt that this inappropriate fun

and frolic must have resounded like

sacrilege to several millions of

Croats who had looked upon Stjepan

Radić, and ubiased observers have

been left under general impression

that effect of these unfortunate

actions could not but be contrary to

better understanding between Western

and Eastern parts of this

Kingdom…And still, this Embassy is

not of the opinion that anyone else

except for Račić himself is truly

responsible for this gruesome

murder, but there is also no doubt

that the manner in which the trial

was handled … strengthened the

standing of anti-Serbian leaders in

Croat masses…I am aftraid this trial

will come down in history as one of

most deplorable cause célèbre in the

history.”

The

above-mentioned report also quotes,

“It is generally thought in Belgrade

that Račić will not serve his entire

sentence (20 years – L.P.) but

could, in fact, be included in

various amnesties the Crown has been

proclaiming from time to time.”24 Such

forecasts turned out to be basically

correct – and actual developments

even more favorable to Puniša Račić.

Out of the 20-year

imprisonment, Račić spent twelve

years in a villa near the Zabela

prison in Požarevac. He had even

moved his family to Požarevac. His

wife was receiving 3,000 dinars from

the Foreign Ministry’s disposition

fund each month. He owned a coach of

his own.

He was formally

released during occupation and the

quisling regime. He moved back to

Belgrade. There are several versions

of way his life ended. According to

one, he went to a mill at the foot

of the Mt. Avala. A partisan unit

tracked him down and shot him dead.

|